Compensation

On a hike, 80-year-old Sydney Lea is confronted by the beauty, cruelty, and surprising heartiness of nature.

...a belief in compensation, or, that nothing

is got for nothing,--characterizes all

valuable minds.

–R.W.Emerson, Ch. II., “Power,” in The Conduct of LifeOne sunny autumn day, I reached the trailer again; I hadn’t been up that little mountain for some time, but not much was changed. Maybe the trailer tilted a bit more, but the trash remained: cans, shards of glass, and dead appliances, which over the years had evidently been flung or shoved out the entry, now doorless. The old site was still a mess, all right, especially in such a lovely wild scene. That morning, however, all the litter looked somehow perfectly arranged, each with its rightful place among the clods and rocks and weeds.

I’ve wondered again and again how that trailer, the pale aqua of a ‘50s Florida motel, ever got hauled up to a landscape otherwise gone back to woods and pucker-brush, its ghostly tote road long since abandoned by loggers. To judge from the girths of trees all around me, the last cut had been ages ago. I can’t say why it made me glad to find the shabby dwelling and all its surrounding trash essentially the same as ever: the mystery of the matter, I suppose, indeed the wonder.

A knobby apple tree stood behind the trailer. I’d originally seen it in grudging bloom one long-gone spring—in fact on my very first hike up there—by looking into that vacant doorway right through the bashed-in back window. I circled around to sniff the blossoms. I’ve never known that apple to flower since. I’d been rarely privileged, it seems.

There’d be no additional harm to me beyond a mild chill if I lingered until morning, but I’d alarm my wife and others who’d care. I’d had a stent put into a coronary artery in 2016 when I was 73 and, though I’d felt fine and fit since, who knew what those dear ones down below might imagine?

On this later trip, before sitting on the ground, I assured myself there was nothing to cut me beneath the tree. I already had a small wound, a lightly bleeding scratch on my wrist from a berry-cane I’d carelessly brushed coming up. “That’s injury enough,” I said out loud and chuckled.

I made the hike I recall in middle October, but it had stayed quite mild. Once I propped myself against the same tree’s scabby trunk, I noticed how its autumn-beige foliage grew overhead as sparsely as its blossoms had that long-ago spring.

I don’t know how long I stayed before I woke up to the fact that so late in the year, it would shortly enough get dark, that I hadn’t set out until well after lunchtime, that I needed to head down. Not that, if I wanted, I couldn’t spend the night on that mossy ground, my only discomfort the few remnants, warm-weather mosquitoes that would soon start to strafe me anyhow, even if I walked briskly. There’d be no additional harm to me beyond a mild chill if I lingered until morning, but I’d alarm my wife and others who’d care. I’d had a stent put into a coronary artery in 2016 when I was 73 and, though I’d felt fine and fit since, who knew what those dear ones down below might imagine?

But why this reluctance to stand and go down in the first place? Well, everything, as I say, even the drying blood-beads on my arms, struck me as handsome and orderly rather than anything else. I didn’t feel any pain. The air was heavy but aromatic, tonic. I imperfectly understood what the Buddhists must feel in meditation. I’d always been too restive to practice meditation for long; but now my obliquely similar state of mind was mostly what fixed me to that earthen seat.

At last, however, I got up and decided, the hour being what it was, I’d take a beeline route to the dirt road where I’d parked rather than treading the ghost of a road I’d come up. My rambles in this country had been countless, so, although I carried no compass, I knew I wouldn’t lose my way.

These countless hikes of mine, these bushwhackings with no ends beside themselves, would end one day, sooner than much later, and what will the point have been?

Yes, “nothing is got for nothing,” as Emerson said. I understood, scarcely for the first time, even if I too often forget it, that even beauty and composure in the world don’t come for free. Whether or not that makes me a “valuable mind” isn’t my business to judge, but halfway downhill, I happened on an instance, perhaps, of what the Concord Sage meant. I saw a predator-killed flicker lying on a muddy wet spot from the prior night’s thunderstorm, its breast torn away, feathers widely strewn. I could make out a three-toed track: small hawk, likely sharp-shinned or Cooper’s. The flicker’s scattered plumage looked gorgeous, just as somewhere the live raptor surely looked itself. The dusk-fall chant of another predator, a barred owl, started up to my west, far enough off that I heard it as plaintive, not clownish.

Some would call me the clown, I knew. These countless hikes of mine, these bushwhackings with no ends beside themselves, would end one day, sooner than much later, and what will the point have been? Or so I suspect some of my friends might ask, the ones who are, or at least regard themselves as being, far more urbane than I.

Well, each to his or her own, but I could almost believe that if such skeptics had ever been on one of my outings, some of them might, like me, retain images: maybe the skimpy but pearly shower of that old May’s apple blossoms, the luminosity of the dead songbird’s feathering, even the glitter and seeming orderliness of the rubbish by the nodding trailer.

The twilight was prowling toward no light at all as I stood there. I caught a certain scent that comes with fall evening. To be sure, a few mosquitoes were starting to drone, but I disregarded them, once again feeling a seductive drowsiness—or more accurately, serenity. All of the more epical themes I’d once imagined for my time on the planet were happily going extinct in my advanced age.

I’d never seen the other tree bear fruit at all. How many more years could it have left? Well, it had obviously clung to life for a long time; I wasn’t about to bet against its survival. Nature’s organisms find a way to hang on for all they’re worth—often more strenuously than some humans do.

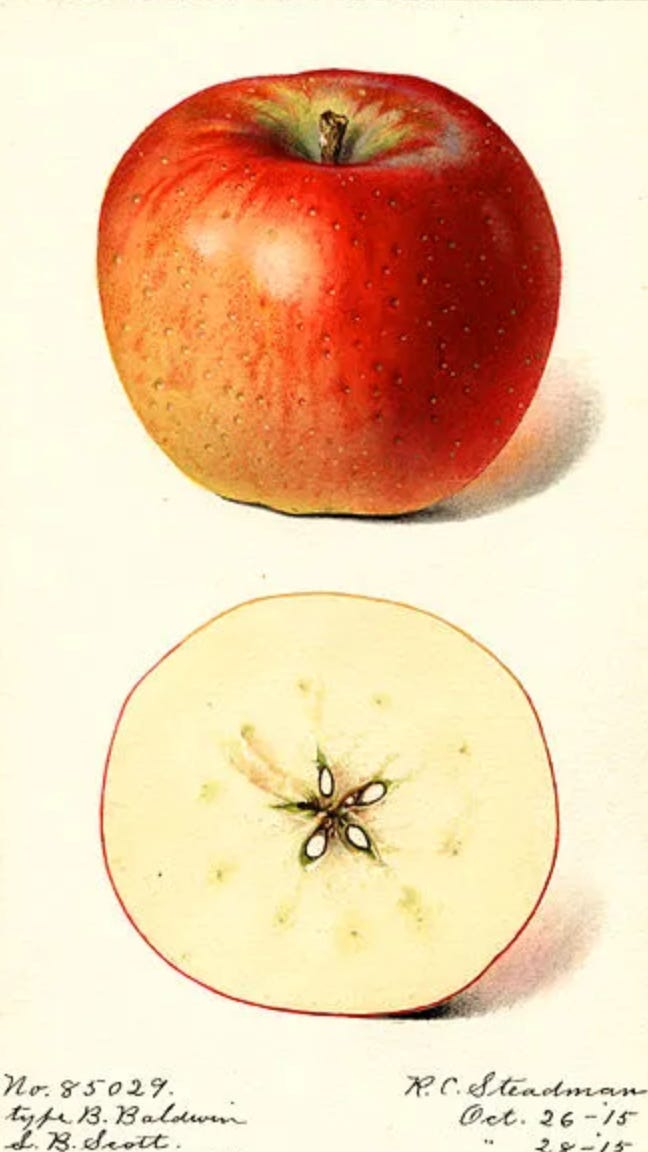

I was awakened from my trance by hearing a gentle thud some ten yards to my left. An apple had dropped from a tree I’d never known was there, one that looked hardier than the one by the trailer. I stepped over and picked up the apple. Baldwin, I surmised, though I’m no expert, something that someone had once planted in these deep woods. Whatever it was, it tasted fine, crisp, just tart enough.

I’d never seen the other tree bear fruit at all. How many more years could it have left? Well, it had obviously clung to life for a long time; I wasn’t about to bet against its survival. Nature’s organisms find a way to hang on for all they’re worth—often more strenuously than some humans do.

The sky was darkening for fair now. I realized I’d really better hurry downhill, all right, and anyway, the next day the world would again be ripe for experience.

oh, this is just lovely writing. it perfectly encapsulates what happens on a good hike: letting the mind wander, making random observations and connections. being absolutely present in the moment, even as it brings up other moments.

You are SO kind! Thanks!!