City of Stars

Michael A. Gonzales recalls close encounters with celebrities in New York City, a place crawling with famous folks.

Back in the late-1980s my Detroit-born friend Chene told me that her adolescent niece was visiting from Detroit when they saw actress Sigourney Weaver on the subway. The teenager got excited and wanted to ask the Alien/Working Girl star for an autograph, but cool auntie discouraged her. “We don’t do that in New York,” Chene explained. Of course, as an autograph hound since I was a kid growing up in Harlem, I sided with the girl, while reflecting on my long-lost collection of famous people’s signatures scribbled on random pieces of paper from mom’s purse.

I got my first when I was 10 years old in 1973, and mom took me to a Central Park concert featuring Little Anthony & the Imperials. Prior to the show, I’d never heard of the group, but that night I got a lesson in the art of doo-wop when they crooned “Tears on My Pillow” and “Goin’ Out of my Head.” Mom’s friend Chuck “Pat” Sherrod played drums and, after the show welcomed us backstage where he introduced me to Little Anthony.

“Did you enjoy the show?” Anthony asked. “I loved it!” I blurted, excited to be meeting a famous person. “Can I have your autograph?” Thankfully mom’s purse was always brimming with pens and paper. Anthony signed the scrap I’d handed him quickly, but with flare. As I would soon discover was common with autographs, the scribble was barely legible. But it didn’t matter.

When we got home I put the signature inside a rainbow-hued photo album, the kind with cellophane and glue on the pages. That book became the keeper of famous inscriptions. Though I didn’t know it at the time, that summer would be the beginning of my Autograph Boy phase. Though more gritty than LaLa Land, my town too was a city of stars and we never knew where or when one might appear.

My friend’s teenage niece wanted to ask the Alien/Working Girl star for an autograph, but cool auntie discouraged her. “We don’t do that in New York,” Chene explained. Of course, as an autograph hound since I was a kid growing up in Harlem, I sided with the girl…

The following month, I’d acquire another autograph when television star Diahann Carroll filmed the movie Claudine on my block. Co-starring James Earl Jones as her boyfriend, the usually glam Carroll plays a working maid, a welfare mother of six kids, who falls in love with trash man Rupert. The scene filmed on my Harlem street was one where Rup takes Claudine to his apartment.

Standing on the sidelines, I noticed that the actress was my crush from the television show Julia, in which she played a widowed single mom and nurse in late 1960s Los Angeles. Thrilled by the sight of her, I ran home for a Bic pen and writing pad. Between takes, Carroll was rushing back to her limo when I popped up and asked. Though usually a shy kid, I had momentarily broken out of my shell. “Can you wait a few minutes,” she asked. “I have to do something.” I would’ve waited forever, but before she got into the vehicle she turned. “Never mind…I’ll do it now.” Her signature was as elegant as she was.

Eight months later Claudine was finally released. I went with friends to our local grindhouse, the Tapia, to see it. Months later, Carroll was nominated in the Best Actress category at the Oscars, but she didn’t win. Still, unlike Black actresses from several generations before, she wasn’t typecast playing maids for the rest of her career. A decade later she was cast as the rich and glam Dominique Deveraux on Dynasty.

Unfortunately, the same couldn’t be said for Gone With the Wind actress Butterfly McQueen, who portrayed the squeaky-voiced slave Prissy. She spent her career serving others on screen.

Thankfully mom’s purse was always brimming with pens and paper. Little Anthony signed the scrap I’d handed him quickly, but with flare. As I would soon discover was common with autographs, the scribble was barely legible. But it didn’t matter.

When mom took me to see Gone With the Wind at an Upper West Side repertory theater in the early ‘70s, I was enraptured by the damn near four-hour epic. Months later, when we boarded the #101 bus on Amsterdam Avenue, I was shocked when I saw Butterfly McQueen sitting next to the window. “Mom, look,” I said, “there’s the lady that was in Gone With the Wind.” Though in her early 60s at that point, I recognized her right away. “I’m going to go ask her for her autograph.”

Before I stood up an older gentleman sitting behind me said, “I wouldn’t do that if I were you. She’s not very friendly.” I stayed seated, but for some reason I slipped into kid mode and imitated McQueen’s voice and most famous movie line. “I don't know nothin’ ’bout birthin’ no babies.”

It wasn’t my intention to make fun, but when a few people started laughing I realized that was exactly what I had done.

Through it all, Butterfly McQueen ignored me and continued to stare out the window.

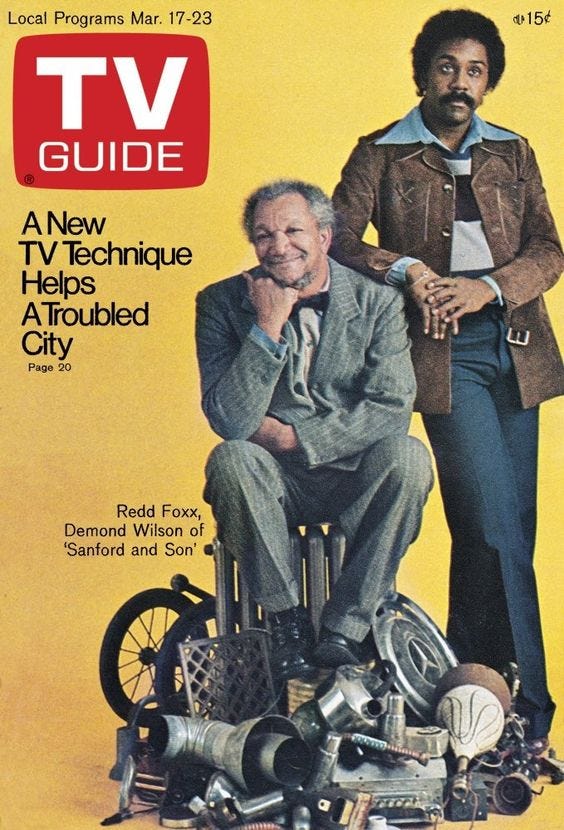

In the winter of 1974, mom and I were again on the #101 bus cruising down 125th Street. Glancing out the window, she screamed, “Hey look, there goes Redd Foxx.” As a weekly viewer of Sanford & Son, I was a fan of the grumpy junk man. After rushing over to the other side of the bus, I saw Redd wearing a stylish suit.

Disembarking at 7th Avenue, I spotted him across the street, chilling in front of the Hotel Theresa. “Do you have a pen and a piece of paper?” I asked mom, knowing she would. Seconds later I was dashing toward him. “Mr. Foxx, Mr. Foxx…can I please have your autograph?” He smiled slyly. “Sure kid.”

However, when I handed him the pen the damn thing was dry. I almost fainted. “I’ll go get another one. Please, wait one minute.” He chuckled. “I’m not going anywhere. I’ll wait.” After burning sneaker rubber running to mom and dashing back, I got my treasured autograph.

I sometimes wonder what drove me to collect autographs, besides the bragging rights of telling my friends I’d met someone famous and showing off my prized John Hancocks at school. Perhaps it was the thrill of sharing space with someone I admired or the surprising realization that entertainers were flesh and blood.

When I handed Redd Foxx the pen the damn thing was dry. I almost fainted. “I’ll go get another one. Please, wait one minute.” He chuckled. “I’m not going anywhere. I’ll wait.” After burning sneaker rubber running to mom and dashing back, I got my treasured autograph.

Certainly it was those brief meetings with famous folks that started led me to reading gossip columnist Liz Smith in the Daily News, buying Rona Barrett’s movie magazines, devouring the teen scene in Right On! and Tiger Beat and watching tele-critics Rex Reed and Gene Shalit.

Once I became a music/pop culture writer in the mid-1980s, I stopped asking for autographs. A part of me thought it was the ritual was silly, but also, if I wanted to be taken seriously as a celebrity journalist I had to rise above the temptation. My inner fan might’ve been screaming and throwing confetti, but when interviewing cartoonist Art Spiegelman, former LaBelle singer/songwriter Nona Hendryx, budding jazz genius Steve Coleman or new jack rapper MC Hammer, I needed to play it cool.

Still, living in the never-sleeps Big Apple, you never knew what notable star might surprise you with a real life cameo appearance ranging from seeing Madonna in Sedutto’s to helping a drunken Brat Packer locate his mother’s Greenwich Village apartment building. Certainly the Upper West Side in the ‘80s was a prime celebrity-spotting area.

I still relish the time I sat next to singer Paul Simon at the movies in 1983. I’d gone to see Love On the Run, a François Truffaut film, at the Regency Theatre on Broadway and 67th Street. When the lead character Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud) told his son if he didn't practice his instrument he'd “become a music critic instead of a musician,” Simon's laugh was the loudest.

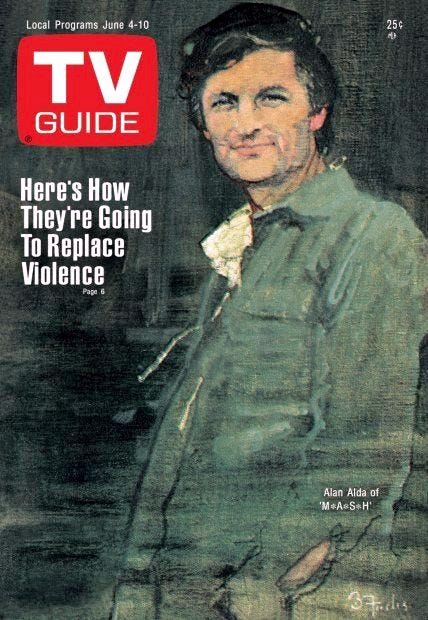

A decade later, when I lived on 90th and Amsterdam, I saw Alan Alda so often I joked with my girlfriend Lesley that he was stalking me. Having grown-up watching M.A.S.H. and considered Same Time, Next Year (1978) a favorite film, it was nice seeing the tall actor in our shared neighborhood. I first noticed him at a bakery on Broadway, then there were a few restaurant run-ins as well as crossing paths when he was walking down Amsterdam.

It got a little weird during Christmas vacation in 1993, when Lesley and I went to Jamaica for six days. On our return flight, I was almost asleep before the plane finished boarding. “Oh my God, look who just got on,” Lesley said. Opening my eyes slowly, I saw Alan Alda stuffing his suitcase into an overhead rack.

I sometimes wonder what drove me to collect autographs, besides the bragging rights of telling my friends I’d met someone famous and showing off my prized John Hancocks at school. Perhaps it was the thrill of sharing space with someone I admired or the surprising realization that entertainers were flesh and blood.

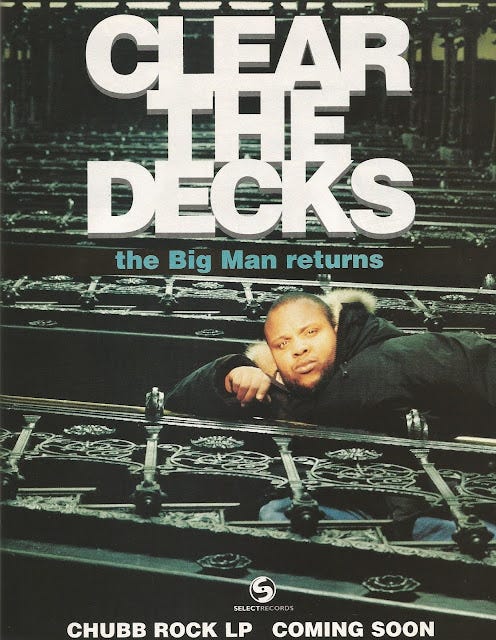

In the winter of 1994 we moved to Chelsea, and the frequency of our encounters with well-known people went up a few notches. Regularly I witnessed actor Ethan Hawke and rapper Chubb Rock coming out of the Hotel Chelsea. I don’t know if they knew one another, but they both stayed at the infamous inn during the same time period.

Chubb Rock was a tall, rotund dude shaped like a black Alfred Hitchcock, who’d had hit singles in 1990 and 1991 with the “Just the Two of Us” and “Treat’em Right.” A Brooklyn native with a personable rap flow, he was light on his feet when dancing in the videos. I once saw Chubb exiting the hotel walking a small dog and chuckled the way I always do when I see big guys with little dogs.

One morning I went to a coffee shop on the corner of 22nd and 7th Avenue, where I was a regular. There was a new kid working behind the counter, a young white guy, about nineteen with a stoner smile. Before I ordered, the young man nervously asked, “Are you Chubb Rock?” I stared at him for a few moments before cracking up.

“Naw, he’s another fat, black guy,” I said. “I can barely talk, let alone be a rapper.”

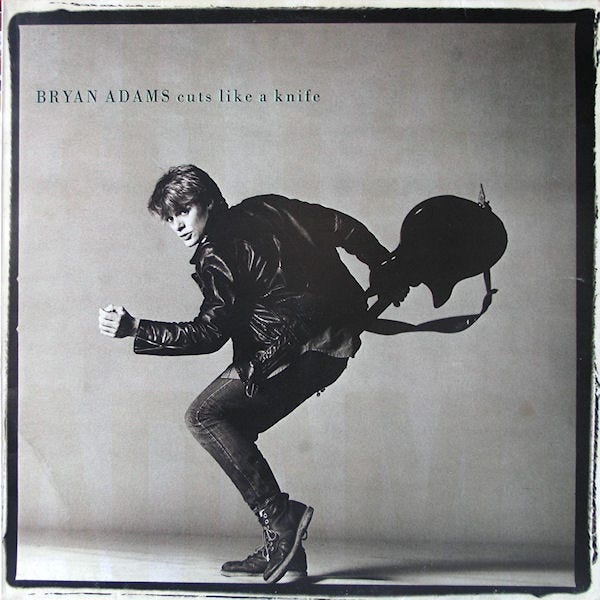

In 1998 Lesley, who was a publicist for Prince, was invited to a birthday party for photographer Daniela Federici. Arriving at the East Village joint where the soiree was held, I noticed there was only one other person there, a handsome guy with a Canadian accent. I had once jokingly told Les, “I love Canada for giving us David Cronenberg, but I will never forgive for them for Bryan Adams.”

Once I became a music/pop culture writer in the mid-1980s, I stopped asking for autographs. A part of me thought it was the ritual was silly, but also, if I wanted to be taken seriously as a celebrity journalist I had to rise above the temptation.

We started talking to the other guest, who was charming and funny as hell. The three of us were having a witty conversation about lateness, photography, pop culture and observations of New York City life. At some point the stranger said, “I remember when my first album came out…”

Before he finished I cut him off. “Your first album; what’s your name?”

“Bryan Adams,” he replied.

Lesley and I glanced at one another knowingly. “You mean, this Bryan Adams?” I asked and leapt into the exact pose he did for the cover of Cuts Like a Knife, the only one of his albums I knew. “Guilty,” he laughed. In addition to being handsome and rich, Adams was a wonderful photographer who’d become friends with Federici through that mutual interest.

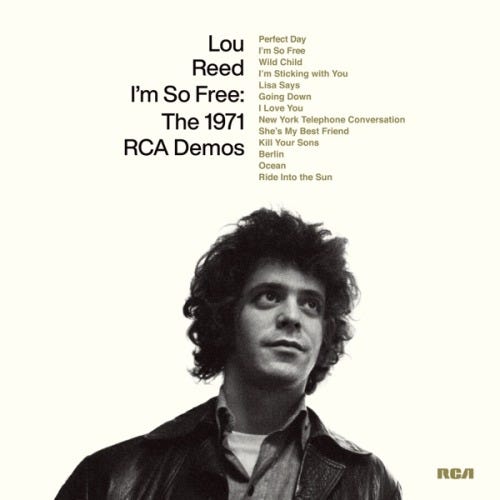

In the early aughts I was walking down the street with my friend and colleague Havelock Nelson (we also collaborated on the 1991 hip-hop book Bring the Noise) when I noticed infamous “Walk on the Wild Side” rocker Lou Reed coming towards us. Star-struck, I told Havelock who I had spotted. "I know Lou Reed. I used to work with him at Masterdisk.” He was referring to a studio where many artists mastered their albums, where Havelock had worked years before.

“Yeah, right and I know Santa Claus,” I joked.

As a Velvet Underground fan since college, I’d read about Reed’s combative behavior and general surliness. As Reed got closer he looked up (Havelock is 6’4”) and screamed, "Hey, Havelock, how you doin' man?" Lou was grinning, truly happy to see his long-lost buddy. When we were introduced, Lou politely shook my hand.

Afterwards, he and Hav talked for a few minutes as they exchanged stories about mutual friends. When he left, Havelock looked over at me and smiled. “I told you I knew Lou Reed.”

In the winter of 2013 I moved to Philadelphia, but came into Manhattan often to go to galleries and concerts. That July I took a bus into the city to see the Philharmonic in Central Park. Having gotten into town early, I was taking a scenic route stroll when I decided to chill on my phone for a few minutes.

Leaning against a parked car on the corner of 75th Street and Amsterdam, I noticed a tall blonde woman walking down the street carrying bags of groceries. As a former altar boy and Cub Scout, I often offered assistance if it seemed needed. “Miss,” I asked, “do you want some help.” She paused and smiled. “Thank you. I would appreciate that.” I relieved her of three of her five bags.

“I’m going to 77th and Central Park,” she said, “is that OK?”

One morning I went to a coffee shop on the corner of 22nd and 7th Avenue, where I was a regular. There was a new kid working behind the counter, a young white guy, about nineteen with a stoner smile. Before I ordered, the young man nervously asked, “Are you Chubb Rock?” I stared at him for a few moments before cracking up.

“That’s fine,” I said. “I’m meeting some friends on 86th Street. We’re going to hear the Philharmonic do the score of West Side Story. That’s one of my favorite musicals.”

Her face brightened. “Mine too,” she replied.

“You should go,” I said.

“I would love to, but I have to go to a work thing tonight.”

“What do you do?”

“Um, I’m an actress.”

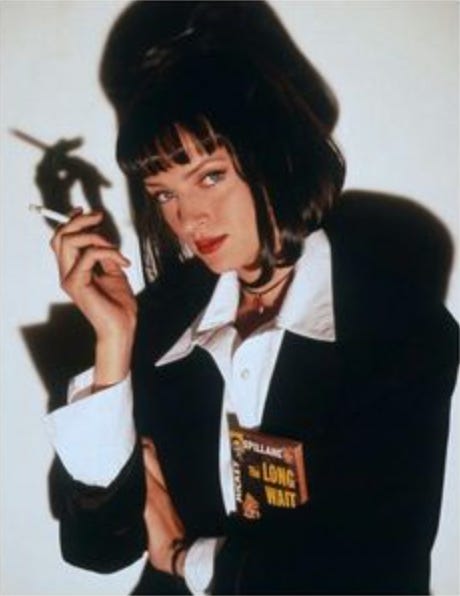

Turning, I looked her directly in the face. It was at that moment I realized that I was talking to Uma Thurman. I’d seen Pulp Fiction and Kill Bill enough times to know what she looked like, but I never acknowledged that I knew. Instead I replied, “That’s cool.” When we got to the middle of her block, she stopped in front of a stately townhouse. “Thank you so much,” she said, flashing her multimillion dollar smile.

The last interaction I had with a famous person happened in 2014 when I went to the Tribeca Film Festival’s opening night party at Providence on 57th Street. I attended with my friend Ericka Blount, a longtime entertainment writer. There were sliders, Hennessy cocktails and disco music blaring.

We made our way upstairs where people were dancing. An attractive woman who stood a few feet away kept glancing at me and grinning. Ericka asked, “Who is that woman that keeps looking over here?”

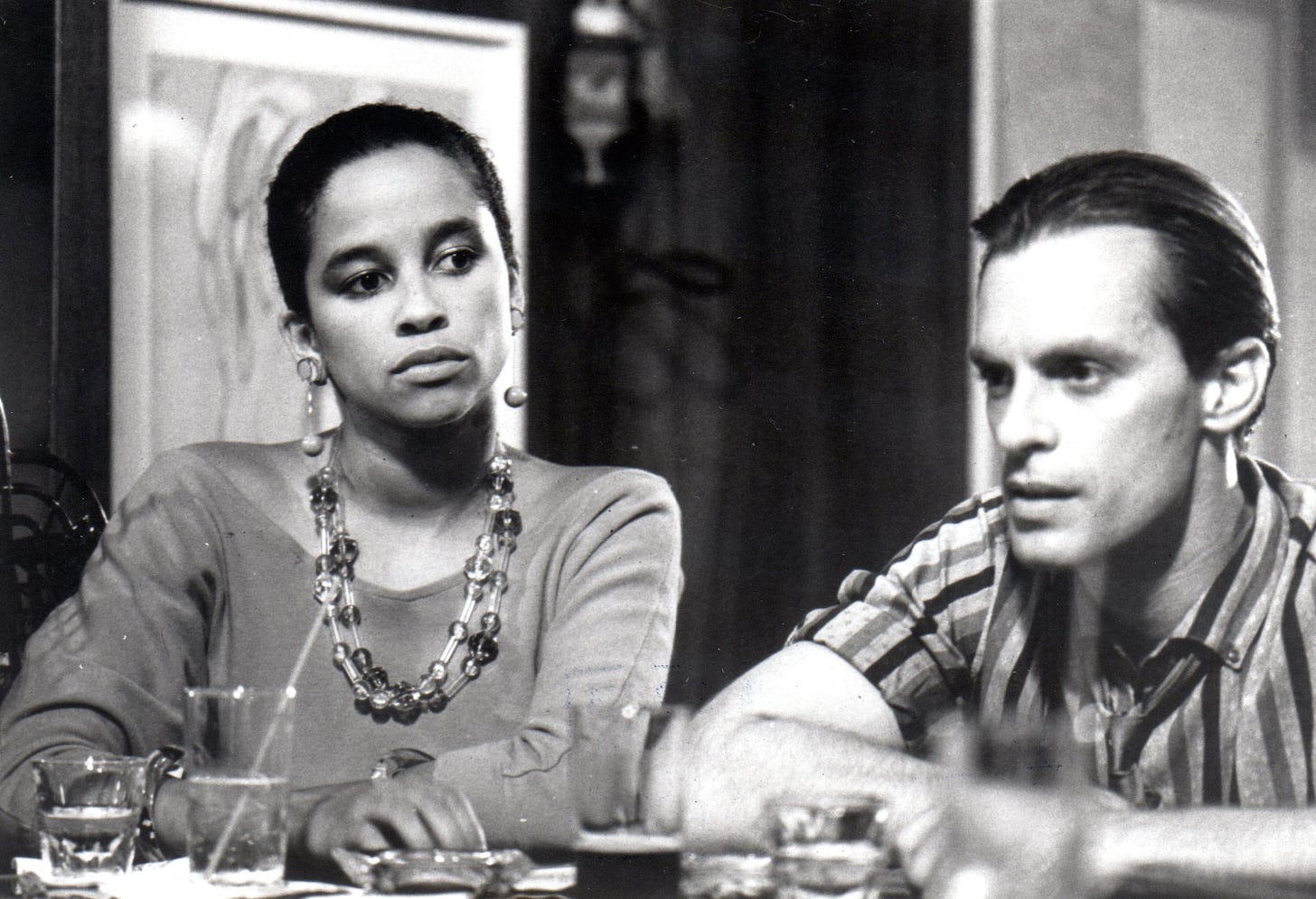

“That’s Rae Dawn Chong,” I replied.

Having not lived in New York City for a decade has largely eliminated my chances of seeing famous folks wandering in the wild. I won’t pretend it wasn’t cool while it lasted. It made for great stories to tell at dinner parties and dive bars, but I had my time, and then it ended.

Years back, she was one of my movie star crushes, who I had admired since 1981 when I saw her in Quest for Fire. Though I’d seen most of her films during that era, including Beat Street and The Color Purple, it was her role as the poet Pearl Antoine in the underrated Alan Rudolph film Choose Me that really stood out for me.

Thirty years later, she was a few feet away smiling. As beautiful as she had been in her youth, I thought she looked even better as a mature woman. As the DJ dropped the needle on Strafe’s classic boogie down banger “Set It Off,” Chong approached me. “Do you want to dance?” she asked. “Yes,” I replied.

Taking her by the hand to the floor, I wasn’t Fred Astaire or James Brown, but I held it down. We jammed through a few songs without getting tired. However, when the DJ slowed down the tempo we stopped. “Thank you,” she said sweetly. “I really needed that.”

“No problem,” I said. “I haven’t danced in front of people in years.”

“My name is Rae.”

“I know who you are,” I replied in the sweetest voice I could muster, with a little laugh. Walking away with her friends, Chong turned around and smiled as she waved goodbye. Twenty years earlier I might’ve lost my mind, but I was cool—though I did laugh when Ericka teased me. “I see you, Mr. Beat Street.” She nudged me in the side and laughed.

Having not lived in New York City for a decade has largely eliminated my chances of seeing famous folks wandering in the wild. I won’t pretend it wasn’t cool while it lasted. It made for great stories to tell at dinner parties and dive bars, but I had my time, and then it ended. Still, every so often I think back to Chene’s niece on the subway three decades ago and wonder how her life might’ve been different had she gotten Sigourney Weaver’s autograph.

I love Michael's memoirs. As I said before, I hope he makes a book of them.

I always tried to ignore the famous people I saw, but one day when I lived on the Upper West Side in the 80s, I saw Kevin Bacon carrying a large mirror on Broadway walking toward me and for some reason, I forgot I didn't "know" him and said, "Hiya, Kevin," as I passed him. "Hi, how're you doing?" he said. A few days later, I came across him again and he was the one who said hi to me. I think he thought he actually knew me. It was embarrasing. After that, whenever I'd spot him, I'd cross the street to avoid him.

That was a great read! My mother used to tell me to not stare or say anything to famous people too. She was a pastry chef at a major hotel in the 60s thru the 80s and many famous people passed through the dining room. She would let me and a friend do tea and I had to school my friend not to stare and act crazy. NYC is tops for anonymity, it why they live here- if you know ,you know.

I bet you live in fishtown if you are still in Philly. Have a house there but my east village crib is home.