Charlie and Me

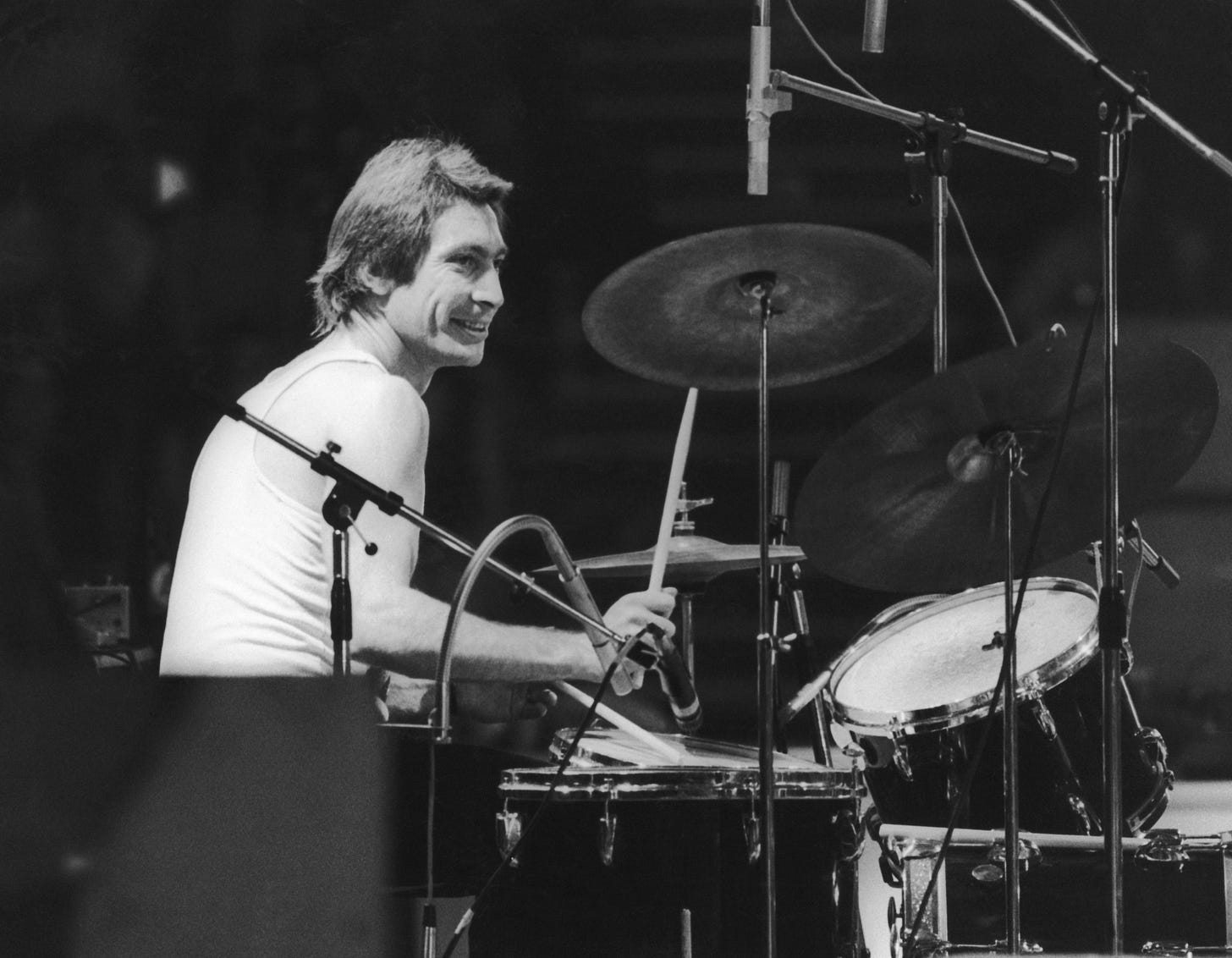

Robin Eileen Bernstein, "a 62-year-old mom who’s been playing drums for nearly five decades," pays homage to the Rolling Stone who inspired her to become a time-keeper as a teen.

I wrote my first love letter in 1967 when I was a skinny, bookish 8-year-old with an overbite. The intended recipient? Davy Jones, lead singer of The Monkees, whose elfin grin, mop-top hair and English accent appealed to girls too young to grasp the genius of The Beatles or the raw sexuality of The Rolling Stones. I don’t recall what my letter said but it may have included a hand-drawn heart.

The next time I wrote to a rock star I was 15—post-orthodontia yet still skinny, bookish, and prone to crushes. But this wasn’t just another billet-doux. It was a declaration to the drummer of the Stones, Charlie Watts, that more than anything, I wanted to be a drummer just like him. This past August, roughly half a century after I put that missive in the mail, I was heartbroken by his death at age 80.

In 1974, the year I wrote that letter to Charlie, my conservative, Nixon-supporting dad insisted over and over, “Girls don’t play drums!” I naively assumed he was right.

His passing inspired thousands of published words by legions of writers, from celebrity musicians to music critics. But there was nothing from a fan like me. Maybe because there aren’t many fans like me: I’m a 62-year-old mom who’s been playing drums for nearly five decades.

One night last year, Charlie the timekeeper extraordinaire magically managed to reverse time, instantly transforming middle-aged me into adolescent me. “Oh my god, the Stones!” I shrieked like a starstruck teen on that chilly April evening early in the pandemic when four black Zoom boxes appeared on my TV during One World: Together at Home, a benefit concert in the fight against Covid, featuring a who’s who of musicians. Each box was identified in an unassuming white serif font: Mick Cam. Keith Cam. Ronnie Cam. Charlie Cam. One by one, each revealed its namesake’s livestream. I was glued to the lower right box that revealed itself last. The one that contained Charlie Watts.

In 1974, the year I wrote that letter to Charlie, my conservative, Nixon-supporting dad insisted over and over, “Girls don’t play drums!” I naively assumed he was right. My mom tried to teach me what she considered the more feminine art of knitting. I can still hear her counting “knit one, purl two.” But I was a wannabe timekeeper and that wasn’t my kind of counting.

Instead, I’d grab a couple of her knitting needles and head down to our wood-paneled basement in Far Rockaway, a then-forgotten slice of Queens south of JFK that dangles into the Atlantic. I’d put the Stones’ Hot Rocks album on the turntable, queued up to Paint It Black. When Charlie started playing, so did I, using those knitting needles to hit imaginary drums and cymbals. I’d crook my right arm over my left—like I’d seen him do countless times—keeping time on my imaginary hi-hat, smiling at imaginary cheers. I can only imagine how pathetic I looked. But with our oversized stereo speakers bellowing full blast, I felt uber-cool. I became Charlie Watts.

Now, 46 years later, here he was on TV playing…wait, what? Air drums! An upholstered white chair was his crash cymbal and three storage cases in a semi-circle became the rest of his makeshift kit. Charlie was doing exactly what I’d done so often all those decades ago: sitting at home, playing air drums with the Stones. In a span of five minutes, he made air drumming supremely cool and an Internet sensation. I was thunderstruck.

I felt an odd kinship with this effortlessly cool guy. He played the way I wanted to—behind the scenes, patiently driving the band with elegance and flair.

Eventually my dad let me take drum lessons, buying me a four-piece blue sparkle set once he was reasonably sure I wouldn’t quit like I had with piano and guitar. I’ve since upgraded my drums, of course, but I still have a simple four-piece kit, like Charlie used. There was no drummer I wanted to emulate more: His loose understated swing, always in the pocket. His relaxed command of the beat. He never broke a sweat, never overplayed. Unlike many rock drummers who hold their sticks overhand for maximum power, he used the jazzman’s traditional underhand grip, as I often do, which gave his backbeat on the snare that satisfying whiplike thwack.

I especially admired that he loved to draw, as I do, contributing his art to the band’s albums and famously sketching his hotel rooms while on tour. I felt an odd kinship with this effortlessly cool guy. He played the way I wanted to—behind the scenes, patiently driving the band with elegance and flair.

Like me, Charlie shunned the spotlight. I asked author Bill German why his tell-all memoir—Under Their Thumb: How a Nice Boy from Brooklyn Got Mixed Up with The Rolling Stones (and Lived to Tell About It) (Random House, 2009)— had so little about my favorite drummer.

“I sensed he was introverted so I never wanted to invade his space,” said Bill, recalling a 1985 recording session when he sat a few feet from Charlie. “He and I made eye contact every so often—it was impossible not to—but he'd simply nod as if to convey this was where he belonged, behind his kit. I was tight with Keith and Ronnie but whenever I'd run into Charlie, I'd never push beyond hello or a handshake. I was more comfortable marveling at him from afar, even when I was inches away.”

What I want is for Charlie to keep being the pulse of the Stones. But drummers get to keep time, not stop it.

Eventually I became a drummer in a rock band—actually, several over the years. I made a few bucks at it, mostly in beer-soaked bars, and I still play on occasion. At one long-ago gig, a drunk guy stumbled up to the stage and blurted, “You’re pretty good, for a girl.” At another, a stranger gave me the compliment I still cherish: “You play like Charlie Watts.”

Oddly, Charlie died the same day as the debut of a new Netflix documentary about drummers, Count Me In, that I’d been looking forward to. But I wasn’t expecting to watch it mere hours after his death. Seeing drummers like Stewart Copeland heap praise on Charlie—"It’s about the groove, dude…that many look for, but few can achieve…”—was like being dropped into an impromptu memorial service that nobody knew they were attending. On a more positive note, several women drummers were featured, including Cindy Blackman Santana, Samantha Maloney, and Emily Dolan Davies, a testament to how far we’ve come in 50 years. And yet, not far enough.

On that early spring evening in 2020, when the soundtrack outside my Manhattan apartment was a ceaseless wail of pandemic-fueled ambulance sirens, the soundtrack inside was Charlie and me playing air drums. He ushered me back in time to my basement in Far Rockaway, but now I was playing air drums with him, live! For five minutes he and I were the band’s double drummers, hitting our imaginary cymbals and that sweet spot on our imaginary snares. Just Charlie and me, hanging at home, keeping time at the same time. It was the highlight of my night, my week and possibly my entire year.

The tune they played that night was You Can’t Always Get What You Want. It was prescient, in its way. What I want is for Charlie to keep being the pulse of the Stones. But drummers get to keep time, not stop it. Charlie never replied to my letter (neither did Davy Jones) but of course, I didn’t need him to. Nor did I need fame and fortune as a drummer. What I needed, then and now, is what he reminded me about that April night and throughout his long, iconic career: That I play drums for the sheer joy of it. And by that measure, I’ve succeeded beyond my wildest dreams.

Hi Robin. Thank you for the great read. Most people don’t or can’t understand how a timekeeper can have a unique snap and swing on his beat like Charlie did. When I try and discuss this everyone goes quiet and let’s it die because they’re limited. Lol oh well you get it and I’m thankful you posted this article on his Under My Thumb Facebook post. I’m up here in Edmonton Alberta Canada and we’re about the same age and I remember 1974 lol and how everyone was expected to act. Good job and I hope to read more of your great stuff. Thank you again