Age Hacker II

At (almost) 71, Richard Grayson reckons with his 95-year-old father’s habit of shaving ten years off his age.

I greatly enjoyed reading Elissa Altman’s “Age Hacker” essay, about how her mother began lying about her age—and that of her daughter—starting the year Elissa turned 50. I could relate to it because I also have a parent who lied about his age.

But my father didn’t pretend to be younger because of vanity. It was more like economic survival in an ageist culture.

It started around the time my father turned 55 and felt he needed to tell his new employer, co-workers and customers that he was precisely a decade younger.

My father didn’t pretend to be younger because of vanity. It was more like economic survival in an ageist culture.

Why just ten years younger? “Otherwise it would have been too hard to do the math,” he told me recently. “I wouldn’t be able to keep my story straight.”

My father had always looked young. When Dad took me to get a library card when I was 3 and he was 28, the librarian at first tried to chase us out, telling him, “Son, I don’t have time for jokes. Take your baby brother and get out of here!” When I was an 18-year-old college freshman in 1969 and had a problem with my student deferment for the draft, Dad came with me to school to straighten it out. The dean we spoke to first assumed he was my older brother. In his 40s and early 50s, my father became a compulsive runner and a vegetarian. He’s always looked boyish, with a slim build and a full head of hair. But my father felt he had no reason to lie about his age before the early 1980s.

He’d spent his adult life working with my grandfather in their pants manufacturing business and later had been an owner of a chain of women’s clothing stores, a Catskills hotel, a racehorse, and a business importing jeans from Hong Kong. He was either the boss or working with relatives or friends, who knew exactly how old he was. But when all those enterprises went under, he and my mother moved from New York City to South Florida.

Why just ten years younger? “Otherwise it would have been too hard to do the math,” he told me recently. “I wouldn’t be able to keep my story straight.”

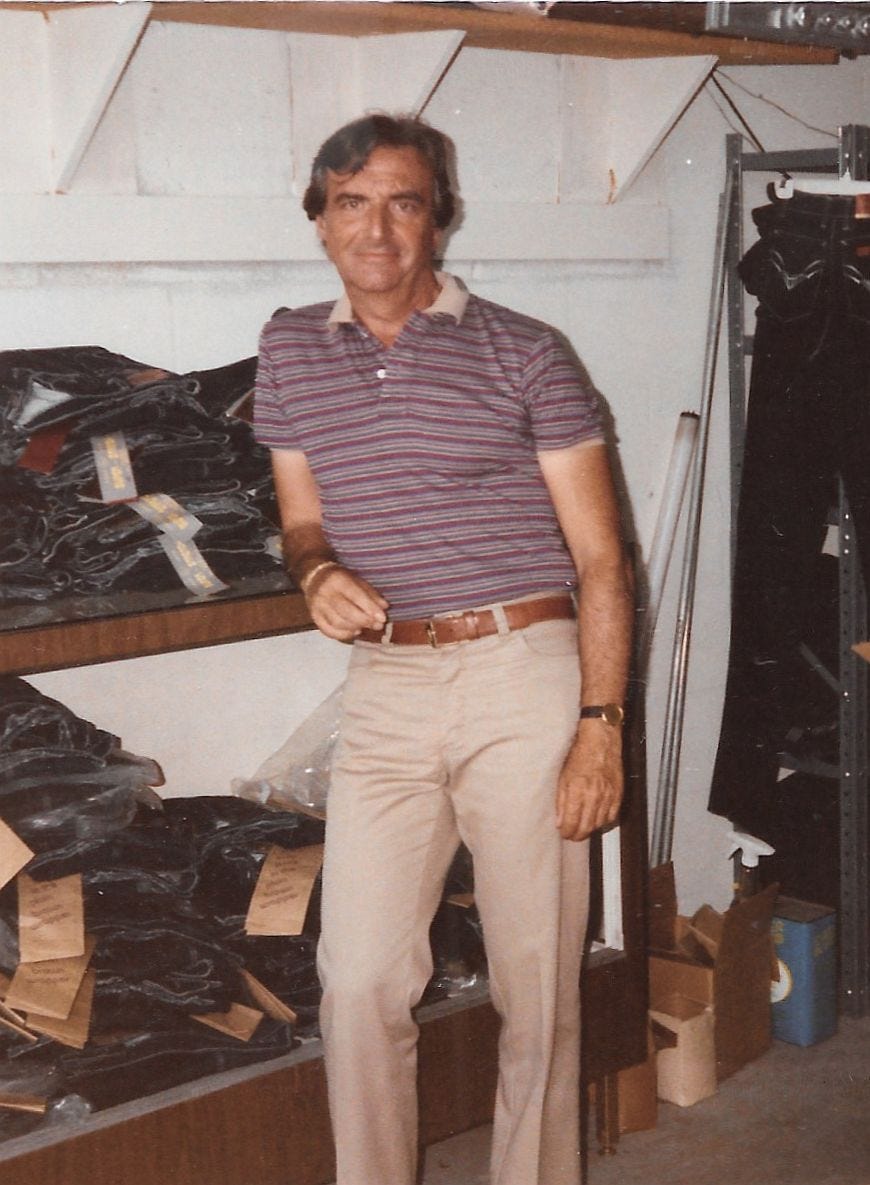

Somewhat desperate for money, he got hired as a sales rep for a company that was the licensee of “hot” (or maybe “cool”?) young men’s clothing lines in the 1980s and 1990s: Sasson, Bugle Boy, L.A. Gear, Guess, Introspect and others. He was selling a product geared to young guys in their teens, 20s and early 30s. He had to wear the fashionable young men’s jeans, tops and jackets when he worked menswear shows in Miami, New York, Las Vegas and L.A. or paid sales calls to department store buyers or retail shops.

Around the house, he wore the same clothes—just like me and my younger brothers, who’d get his free samples after each season’s line had been sold. (Even my grandfather was wearing those free designer jeans in the nursing home—not that he knew it.)

For the next twenty years, my father lied about his age at work—but only at work. My mother, his accomplice, dyed his graying hair back to the jet-black strands of his youth. He also occasionally lied about me, telling people that I was his nephew. It’s not that I didn’t look young for my age, too—much to my annoyance. When my first hardcover book of short stories came out in 1979, the publisher left the back cover blank rather than put the color photo I’d had taken because he said I looked too “babyish.” I started teaching college classes when I was 23, so it’s logical that I was constantly mistaken for an undergrad. But even 15 years later, I’d still get yelled at for using the faculty elevator or the faculty parking lot.

The problem for my father was that my age was a matter of public record: my name and photo were in newspapers a lot and I made appearances on radio, TV and a few magazines. When people asked my father if he was related to me, Dad was afraid that someone might figure out that if I was 32, it was unlikely that he was 47 (when in fact, he was 57). If Dad was 10 years younger, his three sons had to be a decade younger, too. So his youngest son (my brother Jonathan, 10 years younger than I) essentially became his oldest son. I had to become his nephew (presumably the child of his imaginary older brother).

For the next twenty years, my father lied about his age at work—but only at work. My mother, his accomplice, dyed his graying hair back to the jet-black strands of his youth.

Once in the late 1980s, I met Dad for dinner outside the old Coliseum at Columbus Circle, where he’d been working a menswear show. Coming out of building with another sales rep, he somewhat nervously introduced me as his nephew, and I played along.

“Why did you do that?” I asked him when we were alone.

“Force of habit,” he said. “Besides, he might have recognized you from the papers.” I assured him that nobody recognized me, ever.

Eventually, at the end of the 1990s, he lost his job and was forced to become a retail salesman at a chain of mall stores that sold men’s suits. He continued to dye his hair and lie about his age. When he was 71, around the age I am now, he had a massive heart attack at work in the Coral Springs Mall. The paramedics who rushed in to take him to the hospital asked his age, he said, “61,” because he didn’t want his co-workers to know his real age. The next day, visiting him in the ICU, I marveled that he had the presence of mind to lie while facing the prospect of imminent death. “Once I got in the ambulance, I told them the truth,” he said. “I knew I was going to have to show my Medicare card at the hospital anyway.”

A few years later, Dad and my mother moved to Arizona and he got part-time jobs working for the Census Bureau and in a shoe store with one of my brothers. At last, Dad could stop dyeing his hair and go back to being his chronological age. He stopped working when my mother got Alzheimer’s disease and cared for her for the next twelve years until her death.

If Dad was 10 years younger, his three sons had to be a decade younger, too. So his youngest son (my brother Jonathan, 10 years younger than I) essentially became his oldest son. I had to become his nephew (presumably the child of his imaginary older brother).

By the time I reached my 40s, I learned to like looking younger. But it seemed to make more sense to have the pleasure of hearing people say, “No! I never would have guessed you’re that old!” than to lie and try to make myself younger.

My 71st birthday isn’t for another few months, but I’ve already begun telling people I’m that age. (This was a trick my mother’s father taught me.) I’ve never really thought of it before, but I guess that means I lie about my age, too.

At 95, my father still drives, reads several books each week, keeps up with the news and latest trends, and has a girlfriend sixteen years younger. He can easily pass for 80. And he can enjoy a pleasure that was unavailable to him when he took ten years off his age: hearing people say, “No! I never would have guessed you’re that old!”

I started shaving ten years off my age on fitness apps because the workouts for my actual age were limited and too easy but no shaving off years otherwise - yet 😁

People used to think I was 10-years younger, but somehow my looks caught up to reality. Oh well! I really enjoyed your post. Best to you and Dad!