A Jet All The Way

Blaise Allysen Kearsley recalls the high school drama teacher who cast her in West Side Story—a woman she'd hoped would take her under her wing during a trying adolescence.

This essay is one of four sponsored by Revel as part of a collaboration with Oldster Magazine for Women’s History Month. The theme is “The Women Who Came Before Us” and the four authors—Abigail Thomas, Naz Riahi, Emily Rubin, and Blaise Allysen Kearsley—will all participate in a virtual reading to be held on the Revel site on Tuesday, March 8th at 7pm EST.

According to all the cable and Made For TV movies I watched in the 80s, adolescence was the time in a young person’s life when everything worked out perfectly in the end. If you were a teenager with a problem all you had to do was find an adult to turn to, who’d instantly recognize your potential and help you figure out what to do.

So, I imagined that when I got to high school, I’d finally find That Person. That Person: a cool-ass lady whose way of being I could aspire to, who made me believe in what was possible.

That Person would look at me with recognition, because maybe she looked like me—not in features, but in some esoteric, unnamable way. For years, I searched for this whole vibe personified in the face of basically any woman over the age of 18 who walked into any room. Are you That Person? Are you That Person?

That Person: a cool-ass lady whose way of being I could aspire to, who made me believe in what was possible.

I was a rudderless only child, pinched in between my parents’ chaos, an interracial former couple savagely separated, so I wanted That Person to be a mother figure, too. I imagined a metaphysical amalgam of Toni Morrison, Claire Huxtable, Glinda The Good Witch (in both “The Wiz” and “The Wizard of Oz”), Iona in “Pretty in Pink,” and JoBeth Williams as Carol Ann’s mom in “Poltergeist.”

I also imagined high school would be like “Fame”: As Coco, I’d break into song and dance in the cafeteria, then hang out at my locker in a leotard with all my friends, and we’d watch Leroy Johnson, the hottest guy in school, roller skate down the hall in satin gym shorts. In reality, the high school I went to didn’t have lockers. We didn’t even have guys. My nearly all-white all girls school was embarrassingly tiny, and for a private institution, afflicted with a lack of vision and few resources. We were legit known around town as “the lame school,” and no one came to our dances or any of our plays.

All our drama classes had to offer were weird exercises, like inventing and then embodying the sound and movement of a specific kind of make-believe machine, and then your classmates had to guess what your function was, which I found totally pointless and degrading. So tectonics seemed to shift when Margaret “Margo” Daly whirled in as a first-year educator, hired to be the new drama teacher. Ms. Daly ushered in a whole new era in our drama department.

My nearly all-white all girls school was embarrassingly tiny, and for a private institution, afflicted with a lack of vision and few resources. We were legit known around town as “the lame school,” and no one came to our dances or any of our plays.

Under her bubbly but rigorous direction, students memorized monologues from Greek tragedies and wrote their own late night talk shows. She didn’t simply ask us, “If you were a dog what kind of dog would you be?” She, herself, was a whole dog rescue shelter in a 1400-square-foot auditorium—actually just a gym with no athletic equipment. Ms. Daly had tulip-petal lips and a subtle red hue to her short, straight, floppy hair, but she didn’t look like any famous white woman I could think of. She was brought in at the forefront of a handful of young, cool teachers, early Gen Xers. They were so youthful, it seemed as if they could be our friends. When Ms. Daly called out to a girl in the hallway, she even sounded like one of us. I rarely saw her walking from one class to the next without a student by her side. Sometimes she gave us a glimpse of her personal life, joking about the perils of dating; how she was always getting set up by somebody’s mother’s neighbor’s cousin, and how this guy was too full of himself, and that guy wore Bugle Boy pants. I imagined Ms. Daly could be That Person.

Tiny as our school was, I wasn’t in Ms. Daly’s immediate orbit for very long. Despite years of “performance experience” (rigorous dance numbers through the house when I was home alone, and singing The Cure’s “Just Like Heaven” with my best friend Mia on Cambridge streets, Camel Lights burning between our fingers, just to see if strangers would give us money), I was anxiety-riddled and debilitatingly insecure. Since drama was an elective after sophomore year, I elected to sit it out. I was too insecure to take part in public performance situations, especially ones in which things were expected of me and counted on my report card.

Tectonics seemed to shift when Margaret “Margo” Daly whirled in as a first-year educator, hired to be the new drama teacher. Ms. Daly ushered in a whole new era in our drama department.

A part of me still wanted to be in drama class so that I’d feel included, but it wasn’t like I wanted to pursue acting, so it wasn’t worth the trouble. Besides, I already knew I wanted to be a writer. If I did sufficiently well in English, it was due solely to the writing. Not because my writing was good yet, but because I had big ideas, and I wrote all the time.

Still, Ms. Daly was a fixture on the periphery of my compact world. My friends were among her favorite students. Some of them, like me, didn’t even take drama. She invited them over for a pizza party one weekend, which I wasn’t supposed to know about, and I was pretty sure they called Ms. Daly “Margo” to her face, after school.

I was hardly the only one with trouble at home, but maybe mine was more public and looked less surmountable. Maybe it was the perceived difference between “trouble at home” and “troubled.” I was already in deep danger of flunking out. I didn’t discover until decades later that I had ADD Inattentive Type, which meant an inability to focus, trouble understanding directions, illogical thinking and a tendency to forget how to handle tasks I’d done a million times, and a general sense of overwhelm, and Dyscalculia, which meant my brain couldn’t process anything related to numbers. I worked at a coffee shop for six months and at shift’s end the manager would count my register, side-eye me, and say, “The till is off,” which might as well be a life-long metaphor.

She quickly assured us she’d import as many boys of as many ethnicities from other high schools as she could find. Everyone was buzzing. Margaret “Margo” Daly had the balls to do “West Side Story” at a school like ours. And who didn’t love “West Side Story"?

The lack of teacher-student boundaries seemed wrong; it still does. But the high school had a population of only 50 girls and a handful of faculty members fresh out of grad school, so maybe it was unavoidable. While I resented the fact that no overseer kept that shit in check so that no one would feel left out of the fold, I would’ve been fine with the fold if I were on the inside of it. I couldn’t yet articulate the somatic otherness back then—that all those girls were white—or the optics of being the only student of color among my friends, and on the outside of their little group. Or the disillusionment, and how jealous I was of the girls who were kept under Ms. Daly’s wing. I could only wonder what was wrong with me, a resounding question. Was I just a lost cause?

Junior year, my head spun The Exorcist style when Ms. Daly announced our first all-school musical would be "West Side Story,” that epic retelling of Romeo and Juliet set in New York City among rival street gangs in a race rumble. She quickly assured us she’d import as many boys of as many ethnicities from other high schools as she could find. Everyone was buzzing. Margaret “Margo” Daly had the balls to do “West Side Story” at a school like ours. And who didn’t love “West Side Story"?

Some basic concerns worth pointing out here in hindsight: Not everybody loves “West Side Story.” I can’t do math, but I know “zero,” and within the context of our school, Hispanic and Latino representation equaled 0% of the student population. As far as I knew, nobody lived in a tenement building either. That the 1961 movie’s Maria is played by Natalie Wood and her brother Bernardo is played by a Greek-American actor with a caked-on George Hamilton tan to look Puerto Rican didn’t help.

I can’t do math, but I know “zero,” and within the context of our school, Hispanic and Latino representation equaled 0% of the student population. As far as I knew, nobody lived in a tenement building either. That the 1961 movie’s Maria is played by Natalie Wood and her brother Bernardo is played by a Greek-American actor with a caked-on George Hamilton tan to look Puerto Rican didn’t help.

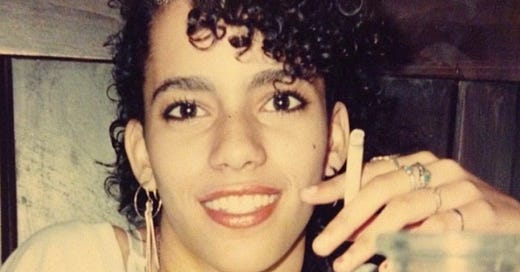

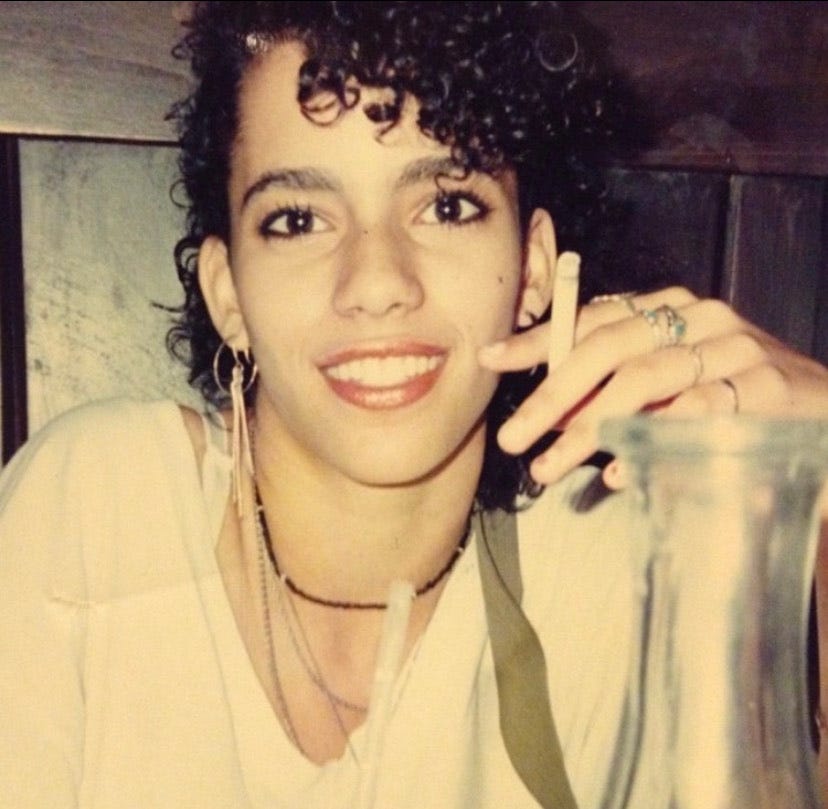

But I’d watched the original film, my mother’s favorite musical, countless times from the time I was in Wonder Woman Underoos. As an ethnically ambiguous kid whose skin color didn’t match that of her dark-skinned father or her white-pink mother, I thought about “West Side Story,” reimagined it, often. Bernstein’s score slithered and swam in my veins. I swooned over the iconic images on the screen—the colors and the choreography were like candy. In my mind I was every character all at once. I already knew the dialogue, the stage directions, and all the finger-snapping sequences, so I could have been a shoe-in. But I couldn’t actually sing, and I’d never auditioned for anything before. The thought gave me the sweats.

I managed to pull myself together at the last minute. Even after a humiliating vocal rendition of “Tonight” in front of the music teacher and Ms. Daly, I was cast as Snowboy, one of the Jets. I threw myself into four months of rehearsals. It felt like important work. I mostly mouthed the words to some of the songs because I didn’t want anyone to hear me, but I was a good dancer and my bad attitude and two-line delivery were on point. Rehearsal was the thing I looked forward to the most, rivaled only by weekends spent drinking, smoking, and making out with boys at friends’ houses perpetually void of parental supervision. The cast was a tight team, a family. During the last of just two performances some of us wept in the wings at intermission, realizing it was half over.

As an ethnically ambiguous kid whose skin color didn’t match that of her dark-skinned father or her white-pink mother, I thought about “West Side Story,” reimagined it, often.

I requested Ms. Daly as my advisor for the following year, my last. It was a last ditch effort to make her That Person. I hadn’t processed that she was just a few years older than my new 22-year-old boyfriend. He was a walking cliché–an actor/musician/flagrant two-timer whom I’ll call Kevin, because that’s his real name. One weekend he said maybe we should break up, then said, I can’t not be with you, then said, let’s just see what happens. I ranted to Ms. Daly about it in an advisory meeting on Monday. She looked exhausted just listening to me.

“What should I do?” I pleaded. “Tell me what I should do.”

She looked down at the desk and said, “I just think you deserve to be with someone who knows they want to be with you.”

No one had ever said anything like that to me before.

I looked out the window and said nothing else. That I might deserve someone who knew they wanted to be with me wasn’t just about a guy. That “someone” was also extended to me. It was about all kinds of relationships. It was about my future. It was about my self-regard.

I requested Ms. Daly as my advisor for the following year, my last. It was a last ditch effort to make her That Person.

I last saw Margo over two decades ago when I was working at an organization that helped middle and high school teachers integrate discussions of racism and antisemitism into their English, History, and Creative Arts programs. I saw her at her wedding. I myself wasn’t invited; I happened to be dating a guy whose Hungarian parents went way back with hers. Everyone was at the wedding: Maria, Bernardo, Riff, almost all of the other Jets, and a few of the Sharks. My old friends who’d been close to Margo in high school were in the wedding party. Ms. Marshall, the cool 11th grade math teacher, asked about the non-profit and I filled her in on my work.

“I’m proud of you!” she said. Then she added, “We always thought of you as The Hellion.” My complicated relationship with that school, with Margo at the center, needled me. I tucked into myself, and kept to the back table with the Hungarians.

Margo and I reconnected last year, during the pandemic, having found each other on social media. Her cheery, casually confident voice sprang from my phone and I could imagine her on the other side of the call pushing her hair back, letting it fall behind her ears in feathered layers, like the shuffle of a deck of cards. We caught up on her life—her role as a teacher, and as the creative director of an award-winning arts center, and as a mother of two teens—and my life: as a writer, teacher, also a mother of two (cats). Then we shifted to our shared history.

“I just think you deserve to be with someone who knows they want to be with you.” No one had ever said anything like that to me before…That “someone” was also extended to me. It was about all kinds of relationships. It was about my future. It was about my self-regard.

“You were a hard nut to crack,” Margo said. “Lots of stomping up the stairs, lots of tears, and contentious parents, and just such sadness. I knew you didn't believe in yourself.”

I heard her shift in her chair and pop a crunchy snack into her mouth.

“But there was this light when you connected,” she said. “I made you a Jet for a reason. I was trying to pull you in to the community. You’d get pissed and you'd push us away. But we knew that. That was part of the job.”

I leaned my elbow on my desk in my work-from-home situation and rested my head in my hand. I smiled.

“There was no way I was going to let you not try out,” Margo said.

Margo wasn’t That Person I looked for, imagined with such longing—whoever that woman was, or could have been. But she came pretty close. Before that phone conversation last year, if you asked what made me decide to audition for “West Side Story” in 11th grade despite my fears and insecurities, I would’ve said I didn’t want to be left out and that I never would have forgiven myself if I hadn’t. I know now that was half of the truth. It may not be an actual memory, but I can visualize Margo poking her head out of a classroom and as I walk down the hall, her eyes follow me. She lowers her chin and asks, “Kearsley, you’re trying out, right.” without the suspended lilt of a question.

This is a fantastic piece. I am your student (Anita). I cannot tell you how much we actually have in common. This information will more than likely surface in the workshop.

“Dyscalculia, which meant my brain couldn’t process anything related to numbers. I worked at a coffee shop for six months and at shift’s end the manager would count my register, side-eye me, and say, “The till is off,” which might as well be a life-long metaphor.”

Thank you for this. I never realized what I have has a name!